Spark

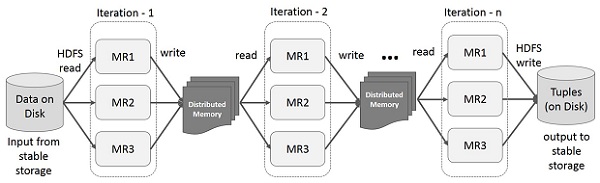

- Key feature: In-memory cluster Computation

- Spark uses Hadoop only for storage purposes

- Has its own cluster management computation

Data sharing is slow in MapReduce due to

- Replication,

- Serialization

- Disk IO

Spark solves this using in-memory computation

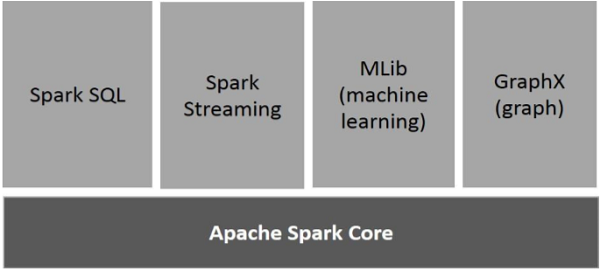

Spark Components

Spark core: Home of the API that defines the RDDs. Spark SQL: Spark Streaming: For realtime/streaming data …

Resilient Distributed Datasets(RDD)

RDDs represent a collection of items distributed across many compute nodes that can be manipulated in parallel.

It stores the state of memory as an object across the jobs and the object is sharable between those jobs. Data sharing in memory is 10 to 100 times faster than network and Disk.

Logical collection of data partitioned across machines

- May be loaded as a reference in External Data Storage systems (HDFS etc)

- Can be created by applying transformations on existing RDDs

Transformations and Actions

Transformations are operations that return new RDDs such as map() or filter()

Actions return a result to the driver program or write it to a storage and kick off a computation such as count() or first()

Lazy Evaluation

One of the core property of Spark is lazy evaluation. Transformed RDDs are computed lazily, i.e. only when you use them in an action

inputRDD = sc.textFile("log.txt")

errorsRDD = inputRDD.filter(lambda x: "error" in x)

warningsRDD = inputRDD.filter(lambda x: "warning" in x)

badLinesRDD = errorsRDD.union(warningsRDD)

The above is not computed yet, as no action has been performed yet

Persistence

If the same RDD is used mulitple times, it is recomputed for each execution. for example, result is computed 2 times for each of the sysouts

JavaRDD result = input.map(x -> x*x);

System.out.println(result.count());

System.out.println(result.collect().mkString(","));

To avoid this, we can ask Spark to persist the data. Once triggered, each executor will store their partition. If a node that has data persisted on it fails, Spark will recompute the los partitions of the data when needed. We can also replicate our data

There are multiple options to persist the RDD

- Scala and Java, the default

persist()will store the data in the JVM heap as unserialized object. - In Python, data that

persist()stores is always serialized - Data written in external storage(disk or off-heap storage) is always serialized

persist() doesn’t itself force evaluation

Spark evicts old partitions using a LRU cache policy.

RDDs come with unpersist() which should be used to manually remove items from the cache.

Key/Value Pairs

PairRdds are a useful building block in many programs as they expose operations that allow you to act on each key in a parallel or regroup data across the network.

eg. join() merges 2 RDDs together, while reduceByKey() can aggregate data separately for each key

reduceByKey()andfoldByKey()will automatically perform combining locally on each machine before computing global totals for each key.

CombineByKey()

combineByKey() is the most general of the per-key aggregation functions. Most of the other per-key combiners are implemented using it. Like aggregate(), combineByKey() allows the user to return values that are not the same type as our input data. To understand combineByKey(), it’s useful to think of how it handles each element it processes.

As combineByKey()goes through the elements in a partition, each element either has a key it hasn’t seen before or has the same key as a previous element.

If it’s a new element, combineByKey() uses a function we provide, called create Combiner(), to create the initial value for the accumulator on that key.

It’s important to note that this happens the first time a key is found in each partition, rather than only the first time the key is found in the RDD.

If it is a value we have seen before while processing that partition, it will instead use the provided function, mergeValue(), with the current value for the accumulator for that key and the new value. Since each partition is processed independently, we can have multiple accumulators for the same key. When we are merging the results from each partition, if two or more partitions have an accumulator for the same key we merge the accumulators using the user-supplied mergeCombiners() function.

example:

sumCount = nums.combineByKey( (lambda x: (x,1)),

(lambda x, y: (x[0] + y, x[1] + 1)),

(lambda x, y: (x[0] + y[0], x[1] + y[1])))

sumCount.map(lambda key, xy: (key, xy[0]/xy[1])).collectAsMap()

… using one of the specialized aggregation functions in Spark can be much faster than the naive approach of grouping our data and then reducing it.

Parallelism

Every RDD has a fixed number of partitions that determine the degree of parallelism to use when executing operations on the RDD.

When performing aggregations or grouping operations, we can ask Spark to use a specific number of partitions. Spark will always try to infer a sensible default value based on the size of your cluster, but in some cases you will want to tune the level of parallelism for better performance.

Most of the operators discussed in this chapter accept a second parameter giving the number of partitions to use when creating the grouped or aggregated RDD.

Repartition: To change the partitioning of an RDD outside the context of grouping and aggregation operations, Spark provides the repartition() function, which shuffles the data across the network to create a new set of partitions. Keep in mind that repartitioning your data is a fairly expensive operation.

If you are decreasing the number of RDD partitions, an optimized version of repartition() called coalesce() can be used, that avoids data movement.

Data Partitioning

Spark programs can choose to control their RDDs’ partitioning to reduce communication. Partitioning will not be helpful in all applications—for example, if a given RDD is scanned only once, there is no point in partitioning it in advance. It is useful only when a dataset is reused multiple times in key-oriented operations such as joins.

Although Spark does not give explicit control of which worker node each key goes to (partly because the system is designed to work even if specific nodes fail), it lets the program ensure that a set of keys will appear together on some node.

Example:

Consider an application that keeps a large table of user informa‐ tion in memory—say, an RDD of (UserID, UserInfo) pairs, where UserInfo con‐ tains a list of topics the user is subscribed to. The application periodically combines this table with a smaller file representing events that happened in the past five minutes—say, a table of (UserID, LinkInfo) pairs for users who have clicked a link on a website in those five minutes. For example, we may wish to count how many users visited a link that was not to one of their subscribed topics. We can perform this combination with Spark’s join()operation, which can be used to group the User Info and LinkInfo pairs for each UserID by key

// Initialization code; we load the user info from a Hadoop SequenceFile on HDFS.

// This distributes elements of userData by the HDFS block where they are found,

// and doesn't provide Spark with any way of knowing in which partition a

// particular UserID is located.

val sc = new SparkContext(...)

val userData = sc.sequenceFile[UserID, UserInfo]("hdfs://...").persist()

// Function called periodically to process a logfile of events in the past 5 minutes;

// we assume that this is a SequenceFile containing (UserID, LinkInfo) pairs.

def processNewLogs(logFileName: String) {

val events = sc.sequenceFile[UserID, LinkInfo](logFileName)

val joined = userData.join(events)// RDD of (UserID, (UserInfo, LinkInfo)) pairs val offTopicVisits = joined.filter {

case (userId, (userInfo, linkInfo)) => // Expand the tuple into its components !userInfo.topics.contains(linkInfo.topic)

}.count()

println("Number of visits to non-subscribed topics: " + offTopicVisits)

}

This code will run fine as is, but it will be inefficient. This is because the join()oper‐ ation, called each time processNewLogs()is invoked, does not know anything about how the keys are partitioned in the datasets. By default, this operation will hash all the keys of both datasets, sending elements with the same key hash across the net‐ work to the same machine, and then join together the elements with the same key on that machine (see Figure 4-4). Because we expect the userData table to be much larger than the small log of events seen every five minutes, this wastes a lot of work: the userData table is hashed and shuffled across the network on every call, even though it doesn’t change.

Fixing this is simple: just use the partitionBy()transformation on userData to hash-partition it at the start of the program. We do this by passing a spark.HashPar titioner object to partitionBy

val sc = new SparkContext(...)

val userData = sc.sequenceFile[UserID, UserInfo]("hdfs://...")

.partitionBy(new HashPartitioner(100)) // Create 100 partitions .persist()

The processNewLogs()method can remain unchanged: the events RDD is local to processNewLogs(), and is used only once within this method, so there is no advan‐ tage in specifying a partitioner for events. Because we called partitionBy()when building userData, Spark will now know that it is hash-partitioned, and calls to join()on it will take advantage of this information. In particular, when we call user Data.join(events), Spark will shuffle only the events RDD, sending events with each particular UserID to the machine that contains the corresponding hash partition of userData (see Figure 4-5). The result is that a lot less data is communicated over the network, and the program runs significantly faster.

Note that partitionBy()is a transformation, so it always returns a new RDD—it does not change the original RDD in place. RDDs can never be modified once cre‐ ated. Therefore it is important to persist and save as userData the result of parti tionBy(), not the original sequenceFile(). Also, the 100 passed to partitionBy()represents the number of partitions, which will control how many parallel tasks per‐ form further operations on the RDD (e.g., joins); in general, make this at least as large as the number of cores in your cluster.

Failure to persist an RDD after it has been transformed with parti

tionBy()will cause subsequent uses of the RDD to repeat the par‐ titioning of the data. Without persistence, use of the partitioned RDD will cause reevaluation of the RDDs complete lineage. That would negate the advantage of partitionBy(), resulting in repeated partitioning and shuffling of data across the network, similar to what occurs without any specified partitioner.

Many other Spark operations automatically result in an RDD with known partitioning information, and many operations other than join()will take advantage of this information. For example, sortByKey()and groupByKey()will result in range-partitioned and hash-partitioned RDDs, respectively. On the other hand, oper‐ ations like map()cause the new RDD to forget the parent’s partitioning information, because such operations could theoretically modify the key of each record.

Operations That Benefit from Partitioning

cogroup(),groupWith()join()leftOuterJoin()rightOuterJoin()groupByKey()reduceByKey()combineByKey()lookup()

Accumulators

When we normally pass functions to Spark, such as a map()function or a condition for filter(), they can use variables defined outside them in the driver program, but each task running on the cluster gets a new copy of each variable, and updates from these copies are not propagated back to the driver. Spark’s shared variables, accumu‐ lators and broadcast variables, relax this restriction for two common types of com‐ munication patterns: aggregation of results and broadcasts.

Accumulators, provides a simple syntax for aggregating values from worker nodes back to the driver program

Note that tasks on worker nodes cannot access the accumulator’s value()—from the point of view of these tasks, accumulators are write-only variables. This allows accu‐ mulators to be implemented efficiently, without having to communicate every update.

Spark automatically deals with failed or slow machines by re-executing failed or slow tasks. For example, if the node running a partition of a

map()operation crashes, Spark will rerun it on another node; and even if the node does not crash but is simply much slower than other nodes, Spark can preemptively launch a “speculative” copy of the task on another node, and take its result if that finishes. Even if no nodes fail, Spark may have to rerun a task to rebuild a cached value that falls out of memory. The net result is therefore that the same function may run multiple times on the same data depending on what happens on the cluster. How does this interact with accumulators? The end result is that for accumulators used in actions, Spark applies each task’s update to each accumulator only once. Thus, if we want a reliable absolute value counter, regardless of failures or multiple evaluations, we must put it inside an action like foreach(). For accumulators used in RDD transformations instead of actions, this guarantee does not exist. An accumulator update within a transformation can occur more than once. One such case of a probably unintended multiple update occurs when a cached but infrequently used RDD is first evicted from the LRU cache and is then subsequently needed. This forces the RDD to be recalculated from its lineage, with the unintended side effect that calls to update an accumulator within the transformations in that lineage are sent again to the driver. Within transformations, accumulators should, consequently, be used only for debugging purposes. While future versions of Spark may change this behavior to count the update only once, the current version (1.2.0) does have the multiple update behavior, so accumu‐ lators in transformations are recommended only for debugging purposes.

Broadcast Variables

Spark’s second type of shared variable, broadcast variables, allows the program to efficiently send a large, read-only value to all the worker nodes for use in one or more Spark operations. They come in handy, for example, if ? your application needs to send a large, read-only lookup table to all the nodes, or even a large feature vector in a machine learning algorithm.

Recall that Spark automatically sends all variables referenced in your closures to the worker nodes. While this is convenient, it can also be inefficient because (1) the default task launching mechanism is optimized for small task sizes, and (2) you might, in fact, use the same variable in multiple parallel operations, but Spark will send it separately for each operation. As an example, say that we wanted to write a Spark program that looks up countries by their call signs by prefix matching in an array.

A broadcast variable is simply an object of type spark.broadcast.Broadcast[T], which wraps a value of type T. We can access this value by calling value on the Broadcast object in our tasks. The value is sent to each node only once, using an efficient, BitTorrent-like communication mechanism.

Optimizing Broadcasts

When we are broadcasting large values, it is important to choose a data serialization format that is both fast and compact, because the time to send the value over the net‐ work can quickly become a bottleneck if it takes a long time to either serialize a value or to send the serialized value over the network. In particular, Java Serialization, the default serialization library used in Spark’s Scala and Java APIs, can be very ineffi‐ cient out of the box for anything except arrays of primitive types. You can optimize serialization by selecting a different serialization library using the spark.serializer property (Chapter 8 will describe how to use Kryo, a faster serialization library), or by implementing your own serialization routines for your data types (e.g., using the java.io.Externalizable interface for Java Serialization, or using the reduce()method to define custom serialization for Python’s pickle library).

Working on a Per-Partition Basis

Working with data on a per-partition basis allows us to avoid redoing setup work for each data item. Operations like opening a database connection or creating a random- number generator are examples of setup steps that we wish to avoid doing for each element. Spark has per-partition versions of map and foreach to help reduce the cost of these operations by letting you run code only once for each partition of an RDD.

// Use mapPartitions to reuse setup work.

JavaPairRDD<String, CallLog[]> contactsContactLists = validCallSigns.mapPartitionsToPair(new PairFlatMapFunction<Iterator<String>, String, CallLog[]>() {

public Iterable<Tuple2<String, CallLog[]>> call(Iterator<String> input) {

// List for our results.

ArrayList<Tuple2<String, CallLog[]>> callsignLogs = new ArrayList<>();

ArrayList<Tuple2<String, ContentExchange>> requests = new ArrayList<>();

ObjectMapper mapper = createMapper();

HttpClient client = new HttpClient();

try {

client.start();

while (input.hasNext()) {

requests.add(createRequestForSign(input.next(), client));

}

for (Tuple2<String, ContentExchange> signExchange : requests) {

callsignLogs.add(fetchResultFromRequest(mapper, signExchange));

}

} catch (Exception e) {

}

return callsignLogs;

}});

System.out.println(StringUtils.join(contactsContactLists.collect(), ","));

| Func Name | We are called with | We return | Function Signature |

|---|---|---|---|

mapPartitions() |

Iterator of the elements in that partition | Iterator of our return elements | f: (Iterator[T]) → Iterator[U] |

mapPartitionsWithIndex() |

Integer of partition number, and Iterator of the elements in that partition | Iterator of our return elements | f: (Int, Itera tor[T]) → Itera tor[U] |

foreachPartition() |

Iterator of the elements | Nothing | f: (Iterator[T]) → Unit |

Running on a Cluster

Runtime Architecture

In distributed mode, Spark uses a master/slave architecture with one central coordinator and many distributed workers. The central coordinator is called the driver. The driver communicates with a potentially large number of distributed workers called executors. The driver runs in its own Java process and each executor is a separate Java process. A driver and its executors are together termed a Spark application.

A Spark application is launched on a set of machines using an external service called a cluster manager. As noted, Spark is packaged with a built-in cluster manager called the Standalone cluster manager. Spark also works with Hadoop YARN and Apache Mesos, two popular open source cluster managers

Driver

The driver is the process where the main()method of your program runs. It is the process running the user code that

- creates a SparkContext

- creates RDDs

- performs transformations and actions

When you launch a Spark shell, you’ve created a driver program (if you remember, the Spark shell comes preloaded with a SparkCon‐ text called sc). Once the driver terminates, the application is finished

When the driver runs, it performs two duties:

-

Converting a user program into tasks

The Spark driver is responsible for converting a user program into units of physical execution called tasks. At a high level, all Spark programs follow the same structure: they create RDDs from some input, derive new RDDs from those using transformations, and perform actions to collect or save data. A Spark program implicitly creates a logical directed acyclic graph (DAG) of operations. When the driver runs, it converts this logical graph into a physical execution plan. Spark performs several optimizations, such as “pipelining” map transformations together to merge them, and converts the execution graph into a set of stages. Each stage, in turn, consists of multiple tasks. The tasks are bundled up and pre‐ pared to be sent to the cluster. Tasks are the smallest unit of work in Spark; a typical user program can launch hundreds or thousands of individual tasks. -

Scheduling tasks on executors Given a physical execution plan, a Spark driver must coordinate the scheduling of individual tasks on executors. When executors are started they register them‐ selves with the driver, so it has a complete view of the application’s executors at all times. Each executor represents a process capable of running tasks and storing RDD data. The Spark driver will look at the current set of executors and try to schedule each task in an appropriate location, based on data placement. When tasks execute, they may have a side effect of storing cached data. The driver also tracks the loca‐ tion of cached data and uses it to schedule future tasks that access that data.

Executors

Spark executors are worker processes responsible for running the individual tasks in a given Spark job. Executors are launched once at the beginning of a Spark applica‐ tion and typically run for the entire lifetime of an application, though Spark applica‐ tions can continue if executors fail. Executors have two roles. First, they run the tasks that make up the application and return results to the driver. Second, they provide in-memory storage for RDDs that are cached by user programs, through a service called the Block Manager that lives within each executor. Because RDDs are cached directly inside of executors, tasks can run alongside the cached data.

Note: In Spark’s local mode, the Spark driver runs along with an executor in the same Java process. This is a special case; executors typically each run in a dedicated process.

Cluster Management

Spark depends on a cluster manager to launch executors and, in certain cases, to launch the driver. The cluster manager is a pluggable component in Spark. This allows Spark to run on top of different external managers, such as YARN and Mesos, as well as its built-in Stand‐ alone cluster manager.

Spark’s documentation consistently uses the terms driver and executor when describing the processes that execute each Spark application. The terms master and worker are used to describe the centralized and distributed portions of the cluster manager. It’s easy to confuse these terms, so pay close attention. For instance, Hadoop YARN runs a master daemon (called the Resource Man‐ ager) and several worker daemons called Node Managers. Spark can run both drivers and executors on the YARN worker nodes.

The exact steps that occur when you run a Spark application on a cluster:

- The user submits an application using spark-submit.

- spark-submit launches the driver program and invokes the

main()method specified by the user. - The driver program contacts the cluster manager to ask for resources to launch executors.

- The cluster manager launches executors on behalf of the driver program.

- The driver process runs through the user application. Based on the RDD actions and transformations in the program, the driver sends work to executors in the form of tasks.

- Tasks are run on executor processes to compute and save results.

- If the driver’s

main()method exits or it calls SparkContext.stop(), it will termi‐ nate the executors and release resources from the cluster manager.

StackOverflow: SQL Query in spark scala size exceeds integer max value

No Spark shuffle block can be larger than 2GB (Integer.MAX_VALUE bytes) so you need more / smaller partitions.

You should adjust spark.default.parallelism and spark.sql.shuffle.partitions (default 200) such that the number of partitions can accommodate your data without reaching the 2GB limit (you could try aiming for 256MB / partition so for 200GB you get 800 partitions). Thousands of partitions is very common so don’t be afraid to repartition to 1000 as suggested.

FYI, you may check the number of partitions for an RDD with something like rdd.getNumPartitions (i.e. d2.rdd.getNumPartitions)

There’s a story to track the effort of addressing the various 2GB limits (been open for a while now): SPARK 6235

For more info on this error checkout this slide